"He spoke of computers with some awe"

Margaret Mead, John von Neumann, and the prehistory of AI

I recently had the chance to discuss my book Tripping on Utopia with the physicist Sean Carroll on his Mindscape podcast. Typically, Sean’s guests are scientists, but he’s also spoken to a range of interesting people in the humanities (one favorite: Adrienne Mayor on “Gods and Robots in Ancient Mythology.”)

In the episode, which you can listen to here, I mentioned a detail I encountered in my research that stuck with me. I think it may be the earliest reference to the “simulation hypothesis”: the idea that the observable universe could be a computer simulation. Wikipedia will tell you that this theory dates to 2003. In an unpublished 1968 interview with Margaret Mead in MIT’s archives, however, we find that the polymathic Hungarian scientist John von Neumann was apparently toying with the idea in the years just after World War II.

I’m currently on paternity leave, and have been spending many an hour rocking our newborn daughter to sleep while reading on a Kindle. Lately, that reading has been in Benjamín Labutut’s The MANIAC — an experimental novel about von Neumann told in bite-sized historical vignettes.

This fascinating book, and the conversation with Sean, made me decide to dig up my photographs of the original interview and transcribe them below.

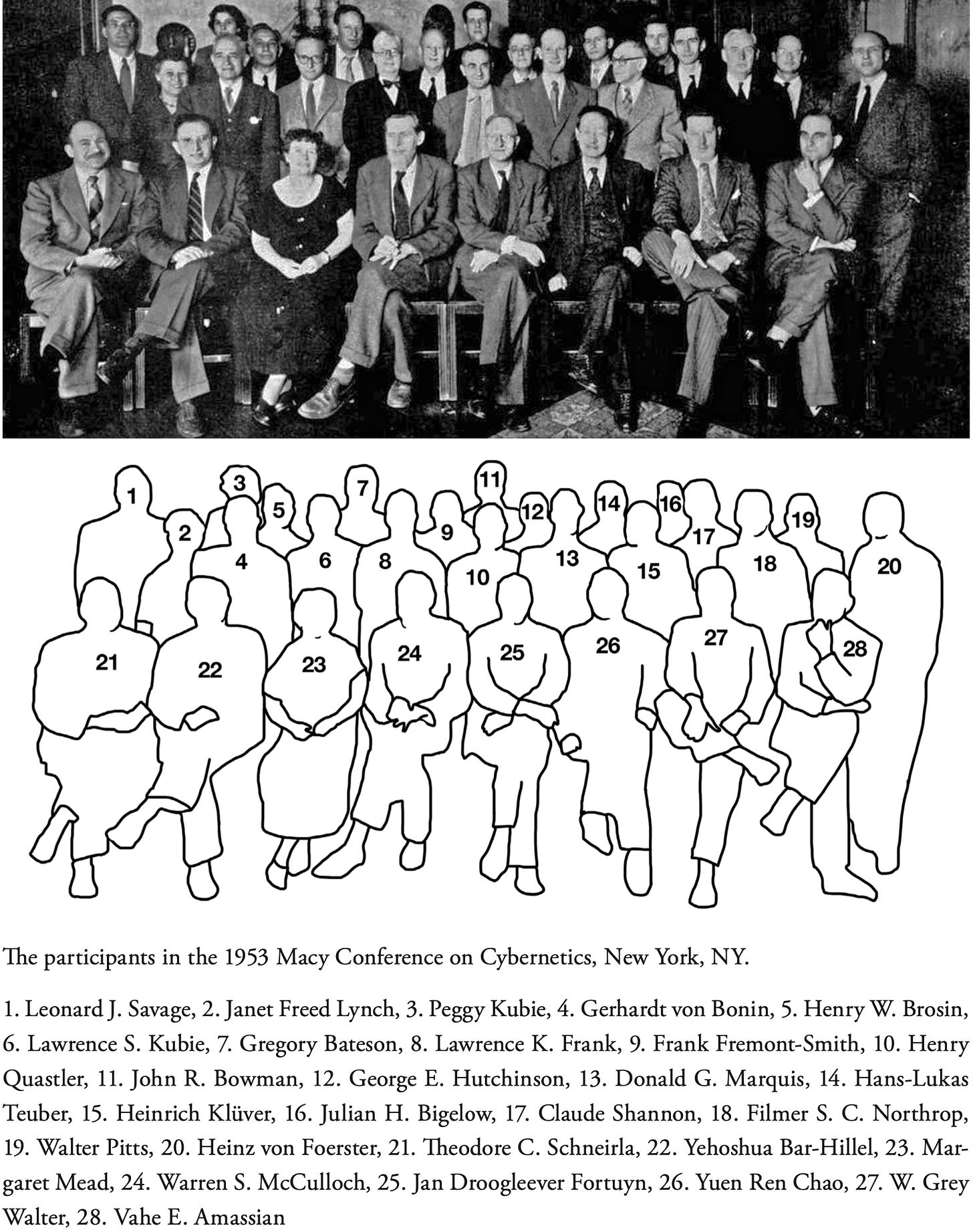

In this 1968 interview with a historian of science named Steve Heims, Mead remembers the Macy cybernetics conferences, which brought together the key social and intellectual group involved in what might be called the “prehistory of AI.” The attendees included von Neumann, Claude Shannon, and Mead herself. Interestingly, there were also several important early psychedelic researchers like Heinrich Klüver (Tripping on Utopia digs into the historical significance of this odd convergence).

When I returned to the original source, I was struck by how prescient Mead was in discussing not just the simulation hypothesis, but also the question of self-improving AI systems. Keep in mind, although her interview was from 1968, she’s discussing events from the 1948-1950 period, when digital computers were just a few years old.

It’s a strikingly interesting historical document that deserves to be more widely read — and, I hope, discussed in the comments below.

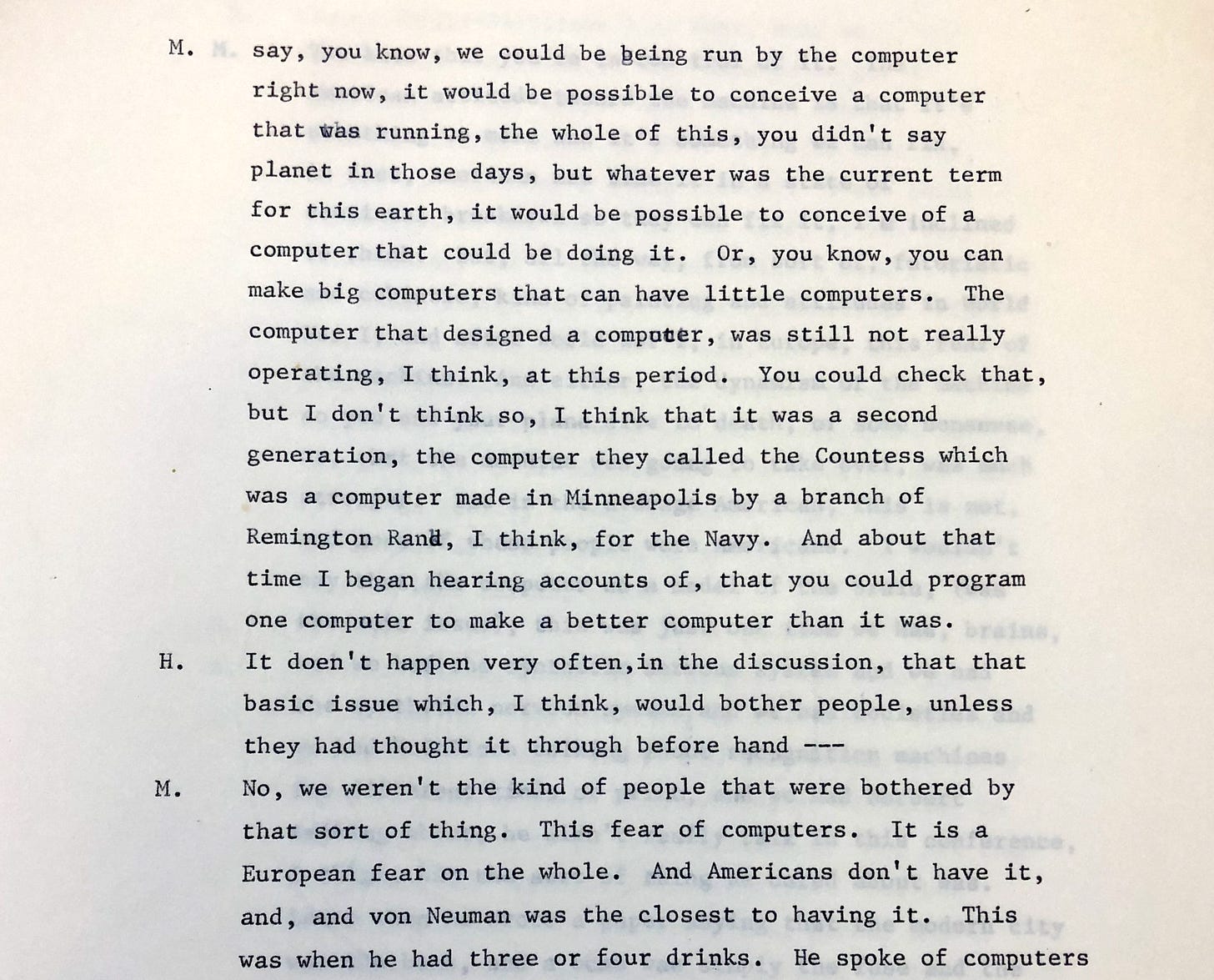

In this excerpt from the transcript, Mead is recalling that the final two Cybernetics conferences (in 1952 and 1953) did not go well. Von Neumann did not attend. But he did have drinks, she recalls, with her third husband Gregory Bateson. Mead then discusses von Neumann’s previous cybernetics conferences appearances, in 1947, 1948, and 1950, and the heady ideas that emerged from them:

STEVE HEIMS: It puzzled me that he was not even listed as a member the last two times.

MARGARET MEAD: The last two times, but Gregory [Bateson] had lunch with him.

H: With von Neumann?

M: With von Neumann. During that conference, and I remember he said, that he said that he said to von Neumann, one thing we do know, that however the brain works, it doesn't work like one of these computers. Von Neumann agreed with him. I mean, I remember just having that reported to me.

H: You know, that’s interesting. I wonder if, if everybody in the conference when it was all over would agree with that.

M: Well, you see, a lot of us never thought that. We simply thought that this was a form of thought. A model building, out of which you could think in a cross disciplinary style. We didn’t think we were making models of the brain. We thought we were developing a cross-disciplinary language which already had a sufficiently good mathematical base so that it might be a viable cross-disciplinary language. Now, that was the major point. I mean, [Norbert] Wiener wasn't primarily interested in making a model of the brain either. He was interested in thinking about systems of this order. But, of course, von Neumann majorly represented, the computer position in the conference. And he would sort of say, you know, we could be being run by the computer right now, it would be possible to conceive a computer that was running, the whole of this, you didn't say planet in those days, but whatever was the current term for this earth, it would be possible to conceive of a computer that could be doing it. Or, you know, you can make big computers that can have little computers. The computer that designed a computer, was still not really operating, I think, at this period. You could check that, but I don't think so, I think that it was a second generation, the computer they called the Countess which was a computer made in Minneapolis by a branch of Remington Rand, I think, for the Navy. And about that time I began hearing accounts of, that you could program one computer to make a better computer than it was.

H: It don't happen very often, in the discussion, that basic issue which, I think, would bother people, unless they had thought it through before hand —

M: No, we weren’t the kind of people that were bothered by that sort of thing. This fear of computers. It is a European fear on the whole. And Americans don't have it, and, von Neuman was the closest to having it. This was when he had three or four drinks. He spoke of computers with some awe. And the real distinction is the people who feel awe for computers. They’re nuts. And if you don’t feel awe for computers, you say, “Look in box 37, that's where the trouble’s likely to be.” Which is the typical American approach to a computer.

H: It has to do with being, feeling that you can repair, that you can work with it?

M: You know that you’re in control of it. The American attitude toward the machine is that it's something we make and it’s something we can fix. In fact, American men like it in a state of continual breakdown so they can fix it, I’m inclined to think. But, all the way, from sort of, futuristic and cubistic, kind of painting and attitudes in World War I, and after World War I, in Europe, [there’s] this fear of the machine. And either the dynamism of the machine so you and your plane dive to death, or some nonsense, or, that the machine was going to take over, was much stronger. But in the average American, this is not [the case]. And most of these people were Americans.

One of the reasons I spent the past few years researching and thinking about Mead is that I find so many present-day concerns emerging in a very early form in her thought and her social world. Here, to my surprise, is an early — very early! — commentary on what has since become the central divide in global AI policy. For the past few years, Europe has been following a very different path when it comes to regulating digital technologies. Whether that’s because of a neo-Futurist, post-WWI legacy of awestruck fear toward technology is another story, of course. But regardless, I’d say Mead was eerily ahead of her time in terms of even thinking about such things back in the 1950s.

I am writing with baby Nava sleeping beside me, which explains the one month break I’ve taken from writing this newsletter. I plan on getting back into a weekly posting cadence in April. In the meantime, I am enjoying reading The MANIAC (which, incidentally, makes for a great companion piece to Oppenheimer).

As I read on, I’ll be imagining what else John von Neumann and Margaret Mead talked about after four cocktails.

Weekly links

• “One of the big turning points in my life was a meeting with Enrico Fermi in the spring of 1953. In a few minutes, Fermi politely but ruthlessly demolished a programme of research that my students and I had been pursuing for several years. He probably saved us from several more years of fruitless wandering along a road that was leading nowhere. I am eternally grateful to him for destroying our illusions.” (Freeman Dyson remembering the moment when Enrico Fermi changed his life)

• “Completed notebooks from the Sol Ross desk are kept at the Archives of the Big Bend... Locals believe that the current desk is the fourth one to occupy this site.” (Atlas Obscura)

• “The Institute for Illegal Images” — an excerpt in The Paris Review from Erik Davis’s forthcoming book Blotter: The Untold Story of an Acid Medium (MIT Press, 2024).

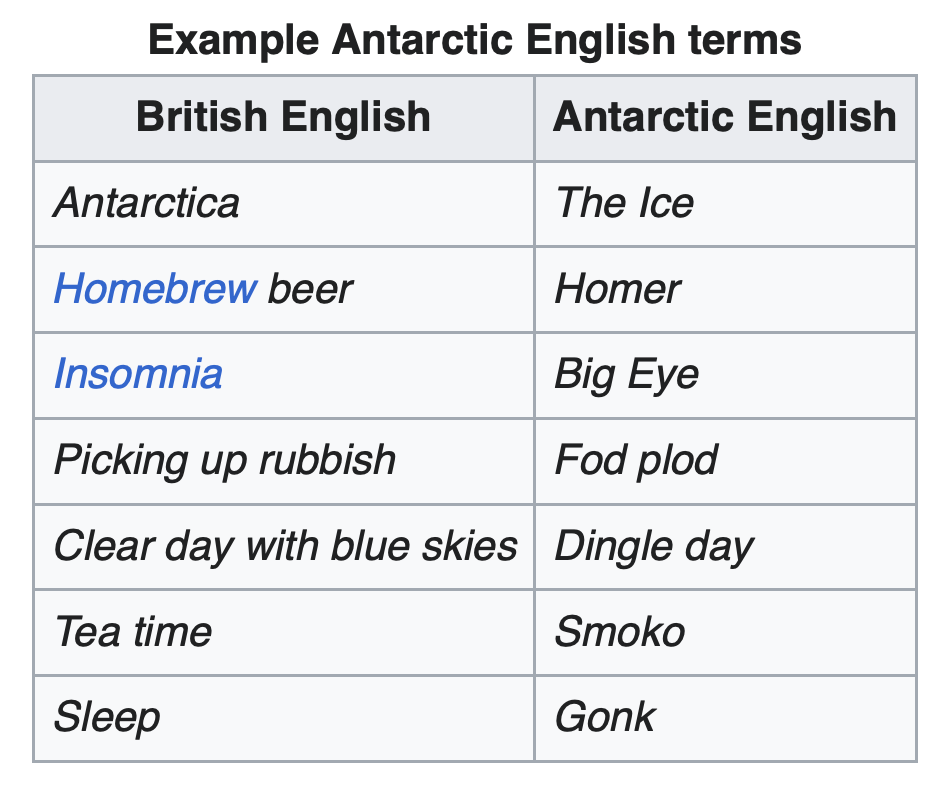

• Antarctic English features various words that are not used in other varieties of English. Differences in vocabulary include:

If you received this email, it means you signed up for the Res Obscura newsletter, written by me, Benjamin Breen. I started Res Obscura (“a hidden thing” in Latin) to communicate my passion for the actual experience of doing history. Usually that means digging into historical primary sources, in all their strange glory.

If you liked this post, please consider forwarding it to friends. I’d also love to hear from you in the comments below.