A few months ago, I was surprised by a delightful email from ‘Marcheto’, the pseudonym of a Spanish science fiction fan and professional translator who runs Cuentos para Algernon (Short Stories for Algernon), a blog where she publishes her translations of science fiction, fantasy and horror short stories she loves with “with the only aim of giving Spanish readers the chance to enjoy them as much as I have enjoyed them”. She continued:

It’s just a small one-person project, nothing fancy, but in spite of that I’ve already published over one hundred great stories by authors such as Ian McDonald, Adrian Tchaikovsky, Aliette de Bodard, Ken Liu, Ian McDonald, Alastair Reynolds, Peter Watts, Dave Hutchinson, among many, many others. Three of them won an Ignotus Award —the Spanish equivalent to the Hugo Award— as Best Foreign Story, and the blog itself and three of the annual anthologies compiling the stories published in the blog also won an Ignotus Award.

Having named some of my favourite contemporary science fiction authors, and with a blog name referencing the title of one of my favourite novels (I wrote a whole piece about it for Nature in 2016), Marcheto asked for permission to translate one of my old science fiction stories, ‘Expectancy Theory’ to publish on her blog. Of course my response was… Are you kidding? I’d be delighted!

‘Expectancy Theory’ is a story with a history. I wrote it in 2001 but after a couple of rejections, I gave up trying to get it published. Nearly a decade later, while working for Nature, I resubmitted it to ‘Futures’, the journal’s science fiction column,1 whereupon it was accepted by the section’s editor at the time, Henry Gee. The story was finally published on 17 March, 2010 in issue number 464, and, much to my amusement, was mistaken for a real theory and cited in a journal article a few years later.

This week, some twenty-two years after it was written, ‘Expectancy Theory’ has been published again, this time in Spanish, as ‘La teoría del desiderátum’. As, depressingly enough, some of you may not have been able to read or even been born when the story was first published, I have reproduced the original version below. It is the work of a young man and I doubt I would be bold or naive enough to write it today, but still, I think the story was rather prescient. I hope it elicits a giggle or two.

If you are waiting for more on von Neumann and Oppenheimer’s relationship, the concluding part of that post will be along in September, by which time I hope to have seen the film in glorious IMAX. If, on the other hand, you are waiting for the conclusion of ‘The Coming of Enki’, the penultimate part of that will with you next week.

Expectancy theory

Wishful thinking.

I conceived then that, irrespective of the brutal history of our species and the multifarious dark, disturbing truths revealed to us in the natural sciences by studies of the human mind and instincts, the world was perfectible. Not through a long, desperate and tenacious struggle against our own fell natures but simply because a large enough number of well-intentioned folk wished it to be.

— Jacques Monad, Journals Vol. III (2003–2006)

Expectancy theory, the scientific hypothesis that ended science and permanently changed the lives of every member of the human race, grew out of a single line of mathematics scribbled down hastily in the journals of the former sociologist Jacques Monad.

At the time of his groundbreaking work, Monad was a 43-year-old tax accountant living in Basingstoke, but he claimed he had drawn the rule out of the surveys he carried out as a PhD student at the University of Liverpool. Although he spent four years conducting research, his doctoral thesis — 'Study of the effects of alcohol consumption on the behaviour of single females: an examination of contemporary Merseyside mating rituals' — was never completed. Monad was thrown out of the university amid claims, always denied by him but, oddly, never contested formally, of scientific misconduct.

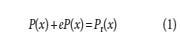

The simple law he formulated — the law of modified probability — still lies at the heart of even the most complex papers of expectancy theory. It can be stated mathematically as follows:

where P(x) is the probability of an event x occurring in the absence of anyone hoping that it will happen, e is the expectancy index and Pr(x) is the actual probability of the event occurring once the full expectation of event x has been taken into account.

It is possible that Monad himself did not perceive the true significance of what he wrote that night. In an interview shortly after his theory was published, Monad said that the law came to him after he had had “a few too many one evening”. A few months later, Monad seemed to have changed his mind. “It was divine inspiration,” he said. “I was truly touched by the hand of God.” A statement he was to repeat many times. The theory's publication history is itself notorious. Rejected by Nature as “a cock-and-bull story that could only have been dreamed up by a madman”, it was swiftly accepted the following week by Science, which in an editorial referred to it as “a landmark”.

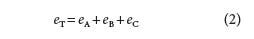

The theory is simple enough but many fail to grasp it immediately because of its counter-intuitive implications. The expectancy index e, in particular, requires further explanation. It is a measure of the effect a human mind can have on the course of natural events by wishing them to be a certain way. In most situations it is, of course, negligibly small. It was found, however, that in certain circumstances, if enough people wish for something to be true, the probability that it becomes true rises significantly. This is because e is a cumulative quantity. Thus if three people, A, B and C, wish for the same event, the total expectancy index eT is a sum of their individual expectancy indices:

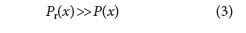

When the total expectancy is a positive value, Equation 1 becomes:

This astonishing result has profoundly changed the way we think about the world and ourselves. Science has largely been discarded as the cheerless product of unimaginative minds. The theory of evolution, a particularly diseased example of the genre, was trashed first. Now we no longer regard ourselves as hairless monkeys desperately trying to cope with a somewhat oversized brain, and as a result we also abandoned the field of sociobiology, with its less than flattering findings about human nature.

In their place, we have adopted a more edifying view: that we are beings designed by an all-powerful intelligence. As a result of certain shortcomings of the human brain, which we are trying very hard to wish away at the moment, the nature of this entity remains somewhat nebulous.

We, as a people, aided by the exceptionally wishful thinking of a few radical feminists, also went on to free ourselves of all gender differences. We no longer have sexual organs, choosing to divide whenever we feel the urge to reproduce. The umbilicus, a vestigial reminder of our undignified past, became our chief pleasure-giving organ. We can now attain orgasm at any time of the day or night simply by prodding ourselves in the navel.

In fact, in the light of Monad's equations, we had to revise the history of science completely, as space and time had warped to fit the hypotheses of physicists. It seemed that science had been a social construct in a way that not even the most devoted advocates of science studies had comprehended. The Universe began to run more like clockwork after Newton wrote down his equations of motion. In retrospect, expectancy theory provides the only explanation of why Einstein's preposterous ideas came to be borne out by experiments. After all, he had remarkable charisma.

Recently, we have abandoned the old systems of governance, which at their most absurd led to a confederacy of unelected oil barons ruling the richest and most powerful nation on Earth. Instead we operate by a new principle: we, the people, get what we want. We are proud of this new arrangement and have named it 'democracy'.

And what has become of Jacques Monad? He has joined the ranks of the immortals. Quite literally, as we all now live forever. Monad has wished into existence a replica of the mansion built by the late-twentieth-century media mogul Hugh Hefner. It is complete in every detail. Puzzlingly, he still chooses to reproduce in the old-fashioned way.

Yes, one of the world’s most prestigious journals publishes science fiction.

That was great. On the subject of science fiction I came across this interesting quote from science fiction writer Annalee Newitz and I wanted to know what you think: “I prefer not to admire problems. But it’s tempting. Especially when you’re dealing with huge systemic problems like climate change or racism, it’s very tempting to sit back and stare at all the multi- layered toxicity and give up. I mean there are a lot of science fiction like that, where there’s bleak nihilistic vibe and humanity lives in a trashcan. It’s a way of saying there will be no future.”