Oppie and Johnny, best frenemies of the Atomic Age. Part I

A fraught relationship helped spawn nuclear bombs and modern computers

Will John von Neumann be the vital piece of the puzzle missing from Christopher Nolan’s forthcoming biopic? I don’t know and, sadly, I will not be able to make it to ‘Oppenheimer’ for a while to find out for sure. I have high hopes that Nolan’s film, released on Friday, will depict Oppenheimer as the complex and conflicted human being he was, a patriot and a Communist, at once proud of his role in sheparding the atom and hydrogen bombs into existence and appalled by the destructive power of the weapons he had helped birth.1 I can think of no film that has succesfully managed to portray a scientist warts and all, and at least one that completely flubbed it. So if Nolan’s film manages the feat, I’ll forgive him for leaving von Neumann out.

But the two men did play pivotal roles in each other’s lives, providing unexpected support for the other when it was most required, and their relationship would, remarkably, catalyse the development of the modern computer, as well as the atom and hydrogen bombs.

Alley cats

Though Oppenheimer and von Neumann had tremendous respect for each other’s talents they were not exactly friends. Says Norman Macrae, von Neumann’s biographer:

Among the great mathematicians and physicists of his time, Johnny apparently intimated to contemporaries that he found a relaxing sense of humor mainly in Fermi and the young Richard Feynman, although also among more personal friends such as Ulam. “But,” said one Nobel Prize winner, “from people like Leo Szilard, or Robert Oppenheimer, or even Albert Einstein, he tended to distance himself (this is my impression).”

As with Einstein, that distancing probably sprang from political differences. Physicist Frederick Lindemann, Winston Churchill’s scientific adviser during the Second World War, said his friend Einstein “in all matters of politics was a guileless child, and would lend his great name to worthless causes which he did not understand, signing many ridiculous political or other manifestos put before him by designing people.”

Von Neumann would have tacitly agreed with that appraisal, and very likely felt Oppenheimer, with his Communist sympathies, was naive too .2 “Johnny thought,” Macrae writes, “that Oppenheimer’s political and economic beliefs were unscientific and therefore regrettable (poor chap).”

Perhaps on these grounds, and Oppenheimer’s proclivity for rubbing his peers up the wrong way, von Neumann would oppose Oppie’s appointment as director of the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in 1947. In a letter to Lewis Strauss, a trustee of the IAS, von Neumann wrote:

“Oppenheimer’s brilliance is incontestable and he would seem to be a most desirable addition to our faculty—if we can interest him in this respect. I have some misgivings as to the wisdom of making him director of the institute, and so have others. I think these matters are better suited for an oral discussion if you would wish me to go into the details.”

Strauss would later be instrumental in stripping Oppenheimer of his security clearance. But on this occasion, he appointed Oppenheimer to head the IAS despite von Neumann’s rather ominous warning.

While von Neumann and Oppenheimer were at Princeton together, “the two men stalked each other like alley cats,” according to one contemporary. But von Neumann would always champion Oppenheimer’s role in the atom bomb project—and dismissed the idea that Oppie would ever be disloyal to his country.

“Robert at Los Alamos was so very great,” von Neumann maintained, “in Britain they would have made him an Earl. Then, if he walked down the street with his fly buttons undone, people would have said—look, there goes the Earl. In postwar America we say—look, his fly buttons are undone.”

One of Oppenheimer’s most inspired decisions would be to invite von Neumann to join the Manhattan Project in July 1943, when the top secret effort to build the atom bomb had reached what turned out to be a critical juncture.

Los Alamos

By the middle of 1943, plans for two ‘gun- type’ weapons were well advanced at Los Alamos. A simple design, such a bomb explodes when a ‘bullet’ of fissile material is fired into another target piece to start a nuclear chain reaction. American chemist Glenn Seaborg had discovered plutonium in December 1940. Like uranium, the new element could sustain a chain reaction but was easier to purify in large quantities. The assumption was that gun- type assemblies could be made to work for a plutonium bomb, codenamed ‘Thin Man’, as well as for the uranium one, known as ‘Little Boy’.

Oppenheimer, however, knew there was a chance that the gun mechanism would not bring together two chunks of plutonium fast enough. If the plutonium being produced for the bomb decayed much faster than uranium, the bullet and target would melt before they could form a critical mass, and there would be no explosion. As a backup, Oppenheimer threw his weight behind another method of assembling a critical mass, proposed by American experimental physicist Seth Neddermeyer, who had earlier helped discover the muon and positron but in later years would conduct experiments to investigate psychokinesis. In principle, Neddermeyer’s ‘implosion’ bomb design was straightforward enough. Arrange high explosives around a core of plutonium, then ensure these charges explode simultaneously to compress the core, which melts: as the plutonium atoms are squished together, more of the stray neutrons in the core start splitting atoms, a chain reaction starts, and the bomb detonates.

Neddermeyer’s team, however, was understaffed and played second fiddle to the gun projects. Furthermore, their early experiments were unpromising…

When Neddermeyer presented his results to the scientists and engineers at Los Alamos, one compared the problem to blowing in a beer can ‘without splattering the beer’. The twenty- four- year- old Feynman, recruited shortly after being awarded his PhD at Princeton, pithily summarized the group’s reaction to the design: ‘It stinks,’ he said. In 1943, the implosion design was therefore regarded as a long shot at best.

—The Man from the Future

Neddermeyer’s team had tried to test the practicality of the implosion method by wrapping hollow metal tubes with high explosive, blowing them up and studying the remains!

Lillian Hoddeson and her co-authors describe the situation in ‘Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos during the Oppenheimer Years, 1943-1945’, curiously the only book on the atom bomb project that describes von Neumann’s pivotal intervention in any real detail:

The early Los Alamos implosion research was remarkably crude. It was carried out in an arroyo on South Mesa. The first test, using tamped TNT surrounding hollow steel cylinders, was made on the Fourth of July (!) 1943, with Parsons attending. The team centered a piece of steel pipe in a larger piece of stove pipe, and after packing granular TNT into the annular space between the pipes, detonated the implosion using Primacord. Other versions of the experiment used powdered TNT and plastic explosive to squash mild steel pipes into solid bars.

Data from one of Seth Neddermeyer's earliest implosion tests. The center ring is an untested cross section of the carbon steel tubing used in the experiment. (From Hoddeson et al.)

The primitive observations made through September 1943 in Neddermeyer's group in the Engineering Division gave early evidence that simple implosion shots were too asymmetrical to release the nuclear energy required for a usable weapon. But few worried about this implosion problem, because the prevailing opinion at the laboratory was that gun assembly would succeed for both uranium and plutonium.

Showing remarkable foresight, Oppenheimer refused to bank on the gun-type weapon. He had surrounded himself by many of the smartest physicists on the planet. But in July 1943, he wrote to von Neumann:

“We are in what can only be described as a desperate need of your help … We have a good many theoretical people working here, but I think that if your usual shrewdness is a guide to you about the probable nature of our problems you will see why even this staff is in some respects critically inadequate.” He asked von Neumann to “come, if possible as a permanent, and let me assure you, honored member of our staff,” and suggested that “a visit will give you a better idea of this somewhat Buck Rogers project than any amount of correspondence.”

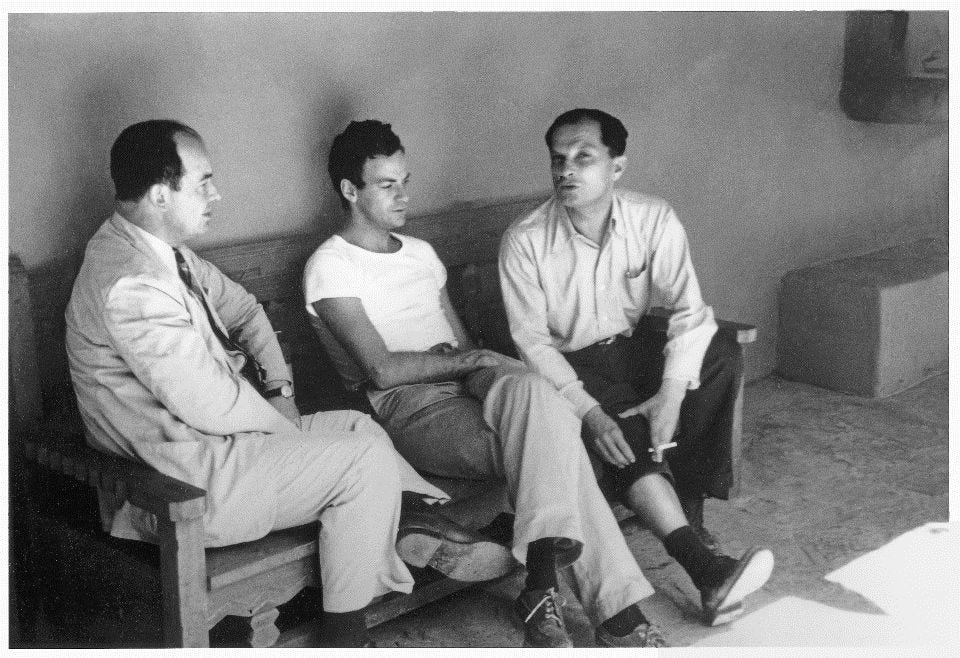

Von Neumann’s first consulting visit to Los Alamos began on 20 September, ended on 4 October and changed the direction of the Manhattan Project. In letters and conversations during the 1930s, von Neumann had predicted another catastrophic war would engulf Europe and during that war, he feared that European Jews would suffer a genocide as the Armenians had under the Ottoman Empire. Shortly after moving to the United States in 1930, he had begun studying the mathematics of ballistics and explosions in readiness for that war and by 1944, had made himself into the world’s foremost expert on ‘shaped charges’.

The shift began with a visit in late September 1943 by the great mathematician and physicist John von Neumann. On learning about Neddermeyer's test implosions of small cylindrical metal shells, von Neumann pointed out that their efficiency could be increased using a substantially higher ratio of explosive to metal mass, which would promote more rapid assembly. The suggestion excited leading Los Alamos theorists, including Bethe, Oppenheimer, and Teller, who could now envision an atomic weapon requiring active material having less mass and a lower level of purity than was needed in the gun device—advantages of particular interest to General Groves…

…the mathematician immediately drew on his recent experience with detonation waves and the Munroe shaped-charge effect to suggest initiating implosion by arranging shaped charges in a spherical configuration around the active material. In this scheme, the jets produced would rapidly assemble the bomb.

Von Neumann's fresh suggestions about implosion, as [mathematical physicist and ballistics expert] Charles Critchfield recalls, "woke everybody up Johnny . . . was a very resourceful man, at least twenty years ahead of his time. I remember Edward [Teller] calling me and saying “Why didn't you tell me about this stuff?”

—Critical Assembly

In the spring of 1944, Emilio Segrè and his team discovered that reactor-plutonium had spontaneous fission rates five times higher than that from cyclotrons (which could not produce plutonium in quantity). A gun-type weapon made with the more abundant, more fissile reactor-made plutonium would not work.

Von Neumann had continued to spend about a third of his time on the bomb. He was perhaps the only scientist with full knowledge of the project who was allowed to come and go from Los Alamos as he pleased. By July 1944, von Neumann and others had worked out the shape of the ‘explosive lenses’ (shaped charges that focus shock waves just as optical lenses bend light) to be used in the implosion device.

A blueprint of the implosion gadget was ready by February 1945—though no one at the lab was confident it would work. Oppenheimer ruled that a full scale test of the bomb was required. ‘Trinity’, based on von Neumann’s design, lit up the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico just before sunrise on 16 July 1945.

‘Fat Man’, essentially the same design as the bomb tested that day, would be dropped on the people of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. Estimates of the death toll vary from 60,000 to 80,000.

“The experience of these two cities,” concluded a study of Hiroshima and Nagasaki written by Japanese scientists and doctors some thirty-six years after the bombings “was the opening chapter to the possible annihilation of mankind.”

Aftershock

A few months later, Oppenheimer would tell Harry Truman, “Mr President, I feel I have blood on my hands”. The remark so angered Truman that it effectively ended Oppenheimer’s chances of influencing the president at all. As Ray Monk relates:

Six months after the meeting, Truman was still railing against the “cry-baby scientist” who had come to his office “and spent most of his time wringing his hands and telling me they had blood on them because of his discovery of atomic energy”.

But Oppenheimer’s reaction immediately after Trinity was quite different: relief and pride in a job well done. As physicist Isidor Rabi recalled:

He was in the forward bunker. When he came back, there he was, you know, with his hat. You’ve seen pictures of Robert’s hat. And he came to where we were in the headquarters, so to speak. And his walk was like “High Noon”—I think it’s the best I could describe it—this kind of strut. He’d done it.

Oppenheimer would later claim that after he saw the blast, he remembered a line from the Bhagavad-Gita:

“Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Yet on the day, Oppenheimer may have revealed his real feelings to the New York Times reporter William Laurence. Asked for comment, Oppenheimer said that the explosion was “terrifying” and “not entirely undepressing”. After a pause, he added, “Lots of boys not grown up yet will owe their life to it.”

Among the staff at Los Alamos, Oppenheimer’s quoting of Hindu scripture caused resentment. With his hand-wringing, was the Manhattan Project’s director sneakily appropriating what was in fact the work of tens of thousands of people? As von Neumann would comment wryly on hearing Oppenheimer’s words:

“Some people confess guilt to claim credit for the sin.”

Thanks for reading. If you found this post enlightening or useful, please share, ‘like’ and consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you’re reading for free. A paid subscription unlocks the Confections & Refutations archive. Comment below or on Twitter @ananyo.

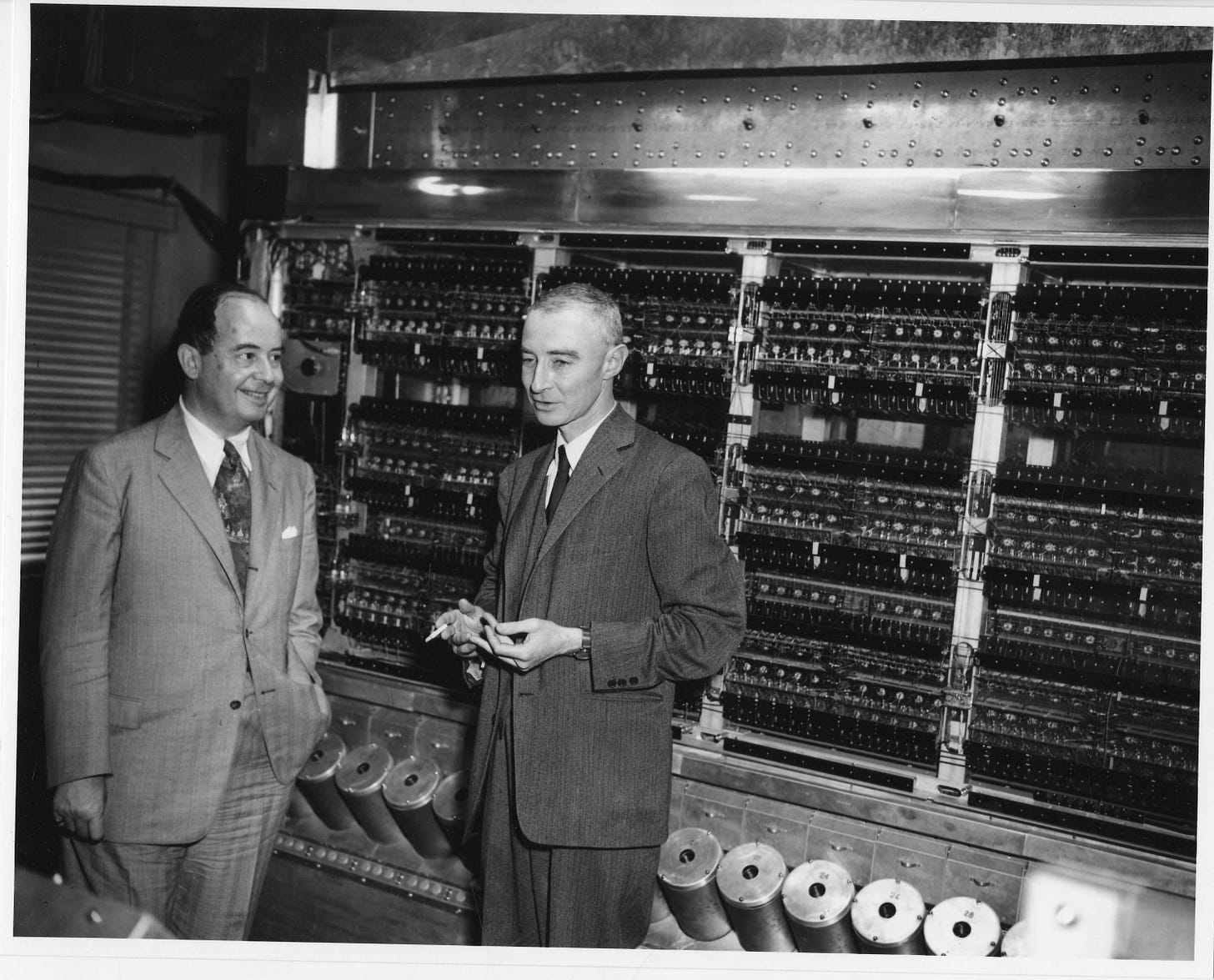

In the next post, I’ll look at the pair’s roles in the development of the hydrogen bomb, von Neumann’s testimony during Oppenheimer’s security hearing and Oppenheimer’s tenure at the IAS, where von Neumann built his computer.

Nolan’s film is ostensibly based on Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s ‘American Prometheus’. Ray Monk’s ‘Inside the Centre’ is another excellent biography of Oppenheimer.

“My opinions have been violently opposed to Marxism ever since I remember,” von Neumann would tell a congressional confirmation hearing after he was nominated to the Atomic Energy Commission, “and quite in particular since I had about a three- month taste of it in Hungary in 1919.”

It might be interesting to note that "Oppie and Johnny" have probably known each other from Gottingen (Germany), where Oppenheimer made his doctorate in 1925-27 and Neumann was on a Rockefeller fellowship on 1925-26. Hermann Goldstine mentioned in his oral history interwiew (https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/107333/oh018hhg.pdf#page=9):

"It was a deep difference between the men. I think it had to do with a lot of antagonisms

that grew up between them when they were students together in Gottingen. I think they were two very bright boys who didn't get along too well"

The absence of John Von Neumann from the Oppenheimer movie does not appear to be related to his friendship with Oppenheimer. After all, Edward Teller, who was not a friend of Oppenheimer I guess since he testified against him during the security clearance hearings, is presented in the film.

Recently, I read a book called "BOMB," which tells the story of how Soviet spies stole the atomic bomb secrets from Los Alamos (the book is very nice after all and I suggest reading it). The book also includes a description of how the bomb was made, mentioning implosion, an idea suggested by Von Neumann. However, despite his contributions, Von Neumann's name is not mentioned in the book.

The explanation for both cases, in the movie and the book, may be due to Von Neumann not being well-known to the wider public at the time. It's worth noting that he passed away around the same period when he was starting to gain fame. His article "Can We Survive Technology?", was the only one published in a popular magazine (he published many articles in scientific magazines and of course he was well recognized by scientists around the world he wrote also remarkable books ) . Probably If he had lived longer, he might have become more widely recognized.